INTRODUZIONE

Of half Chinese and half English parentage, I grew up in Hong Kong. It’s a smelly, noisy and hectic city; the name translates rather romantically as ‘fragrant harbour’ - really, it is anything but. Most people who visit are completely overwhelmed by it.

My childhood memories are tinged with the smell of food cooking street-side, mingled with traffic fumes and garbage. Add to this heady mix the whiff of petrol from the sampans and ferries gathering in said harbour, and they blend together to make an unforgettable atmosphere. In summer, the temperatures reach a high of 35°C (95°F) with humidity only known in sub-tropical countries; when visiting recently, as my hair turned into a bird’s nest, I wondered how I coped. I imagine I was less concerned about how I looked back then.

Growing up, some of my peers lived a more sterile life in townhouses in exclusive areas, their parents being ex-pats sent by their employers with expense accounts to pay the sky-high rents. When visiting, I was fascinated by the stairs they actually had in their houses. We were the opposite; my father moved to Hong Kong in the early ’80s on a whim and my mother was a local. We lived just about everywhere on Hong Kong Island - from a relaxed, beachside apartment in the touristy Stanley area, to high-rise housing estates in Aberdeen and most memorably the grimy confines of Causeway Bay. My daily trip to school involved negotiating the dank, dark corridors of our apartment block, lit by flickering fluorescent lights, and then waiting at the bus stop early in the morning while butchers ferried carcasses down the streets, wearing them like a grotesque piggyback.

Although Hong Kong was a bustling place, it was safe on the streets and from a young age I was given absolute freedom of it. Outdoors in the stifling heat just off the busy roads, men and young students alike would sit on plastic chairs slurping up noodles, steam rising to their faces. Vendors sold fish balls on sticks, the charcoal enticing you in, finishing them with a lick of curry sauce and a shake of chilli powder while you impatiently waited for them to be cool enough to eat. We would spend weekends getting on the ferry to Lamma Island to gorge on seafood, and I would pretend to be the hand of God as I gleefully picked out a doomed fish from the tank to be freshly dispatched for our lunch. My favourite dish was clams freshly stir-fried with black beans, garlic and chilli. I’d suck the flesh out of one half of the shells, sauce dribbling down my face and staining my T-shirt. Like most Chinese kids, we were brought up to be ultimate eaters, and not much made us squeamish.

Roadside shacks with corrugated-iron roofs, dark and noisy within, served French toast piled high on melamine plates - bread dipped in egg and deep-fried, a jug of golden syrup to pour over it at the table. At lunchtimes, businessmen would fling their ties over their shoulders while ladies folded napkins on to their laps to come away pristine and ready to go back to work. Strong tea made with sweet evaporated milk and then poured at a height to make a frothy top was how I learned to love caffeine.

Strip-lit cafés served junky instant noodles in salty broth, perhaps topped with a slice of fried SPAM, or a fried egg nestling on top. I still love SPAM, as you might come to realize. The best chicken you could eat came from places like this, fried with a drizzle of soy sauce and a slick of ginger and spring onion oil. It was for everyone - the poor, the wealthy. Everyone in Hong Kong had a passion for food.

This wasn’t just food you’d eat as a guilty pleasure; it was part of Hong Kong culture.

Sundays were spent in cavernous, brightly lit restaurants for the family dim sum brunch. Back then, my grandfather would arrive first, far earlier than everyone else, to nab the best table. He’d read the paper, sip tea and snack on a few spring rolls while our family gathered in dribs and drabs, noisily greeting each other and settling into their seats. Trolleys full of steamers wheeled past, their drivers calling out their contents. I would poke my head inquisitively in their direction and the ladies pushing them would cock a lid so that I could steal a glimpse of inside. I’d gaze wide-eyed, nose wrinkled as elder aunties would choose a braised chicken’s foot from the steamer for their bowl, only to suck all the skin off the bones and then delicately but deliberately spit all the bones out on to the tablecloth, chopsticks sometimes guiding the way. It was a real art, honed by many years of practice and one I haven’t yet mastered but perhaps something to look forward to in later life. The lazy Susan piled high with dishes constantly revolved and I soon learned not to spin it before my time; a sharp rap on the knuckles with a chopstick was all it took.

My grandmother lived with us for many of my formative years. She’d get us out of bed in the morning with a devastating wrench of the duvet cover, tell us off when my sister and I fought and take us for secret snacks at McDonald’s. If ever we expressed a particular fondness for an after-school snack, that was it; it would be ours every day until we pleaded for something new. Often we’d go to the wet markets with her. The people manning the stalls were all familiar friends and they’d coo over my sister and ruffle my hair, teasing me for looking like a boy with my bowl haircut (thanks Mum). My grandmother would wander from stall to stall, selecting the fresh vegetables and picking up still-wriggling fish to inspect their freshness. A finger pointed at a particular chicken pacing nervously in a cage would mean the end for it; she always instructed me to look away when it was dealt with, and I disobeyed only once. The chicken soup that evening was difficult to swallow.

In the kitchen, though, we were often shooed away. Hong Kong kitchens are never spacious - there were always pots and pans bubbling away, a wok sizzling, a rice cooker steaming. We were relegated to the living room to be amused by the television. I learned no culinary skills from my grandmother, much to my dismay, but what was imparted to me was the joy of eating.

I moved to the UK when I was 13 and I soon realized that the food I grew up with was unobtainable in rural Suffolk. My poor mother was left to fend for herself in a foreign country with two children while my father tied up all the paperwork back in Hong Kong, and not being much of a cook herself and rather homesick too, we ate a lot of Chinese takeaway. We were aghast by the nuclear-orange sweet and sour chicken, and repulsed by the sickly-sweet crispy chilli beef, but at least some of the noodle dishes were passable and others that were served with rice. I threw myself into British life. Those dishes now hold a special place in my heart.

By the time I left home at 18 and moved to London, I really did miss the meals of my childhood. Nostalgic flashbacks would come unbidden. On some winter days,

I wouldn’t be able to get the thought of tender, melting beef brisket slow-braised with star anise and cinnamon out of my head. Other times I actively craved that sunshine-yellow egg custard tart; I’d positively drool over the memory of still-warm flaky pastry, the just-set custard dissolving in my mouth. It was unbearable.

So I began researching recipes for those dishes I missed, from comforting home- style cooking to fancier restaurant dishes. This took me to the heart of Chinatown, and tentatively I studied labels on jars, bought odd-looking ingredients on a whim and had to look up how on earth I’d use them once I got home. It was an experimental and lengthy process, but I fell in love with the Asian supermarkets. Not only did they provide me with access to delicious food, each trip was a trip down memory lane - I could pick up particular brands and squeal ‘I remember this!’

I started my blog, Hollow Legs, in March 2008 so that I’d be able to document the recipes I was discovering. The name came from a nickname my parents gave me for my insatiable appetite (commonly known as greediness). I trawled forums, blogs, recipe sites and the like to get an idea of the recipes I was after so that I could experiment with them all, borrowing ideas from some and embellishing others with my own touches - often, more chilli was added to spicy dishes, more vinegar to sour. My taste buds seem to love those flavours the most. Slowly but surely I learned to cook. It was very much trial and error - a LOT of error, aided by some cursing - but the Internet is a wonderful thing. YouTube videos showed me various cooking techniques, while other blogs with step-by-step instructions or pictures helped me out with the rest. The Asians are a keen bunch, not only loving their food but having an incredible desire to share their recipes.

Over time, I grew more adventurous; I branched out into other cuisines such as Korean, Japanese and Thai. Though I admire Western cookery and I am seriously fiendish for pasta, it never quite took me as much as Asian food did, and still does.

It fascinates me; bright, perky, in-your-face flavours dominate the Asian cuisines, and they take no prisoners. Several trips to Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore cemented this fascination, while the Asian supermarkets, be it in Chinatown or online, enabled me to make the recipes I loved the most at home in the UK.

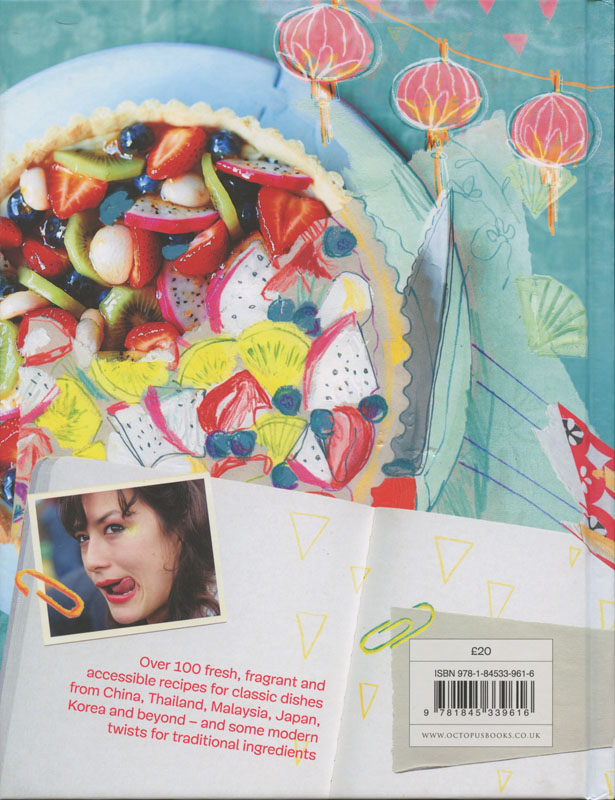

This book is a guide to the Asian supermarket and the treasures you can find within. The supermarkets themselves are often described as intimidating, daunting or confusing. They’re usually big spaces, packed with packets, jars, tins and spices in varying degrees of comprehensibility. My hope is that in sharing the main attributes of common ingredients via the recipes here, the intimidation will lessen and you will gain confidence in Asian food, as I did.

This isn’t supposed to be an educational tome, tangled in the authenticity of cuisines. There are some classic recipes remade to my take in here, but you’ll also find that I’ve downright rejected authenticity in a couple of the recipes to make way for what tastes good - that’s what it’s all about, isn’t it? It’s what I hope to be a fun, accessible book that showcases ingredients used often in Asian cookery.

Each chapter has a list and summary of things you might find in each aisle - a sort of index, so that after a quick glance for reference you can find what you’re looking for more easily or which category something belongs in.

I can’t say that after cooking from this book that you will become an expert in Asian cuisine (is anyone, really?), but that isn’t really my intention either. What I hope for is that you’ll feel the excitement I get when I walk into an Asian supermarket; a sense of flavoursome possibility, and a feeling of adventure in experimenting with everything inside them.

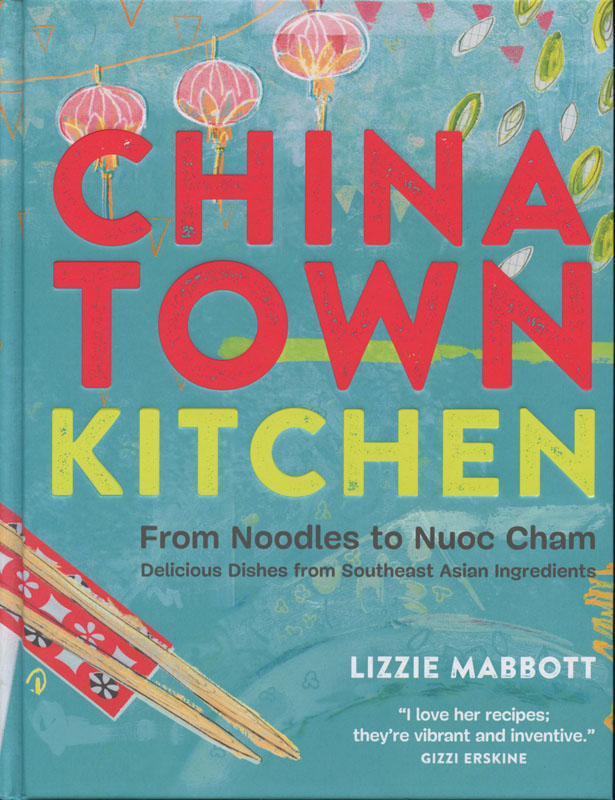

COPERTINE

INDICE GENERALE

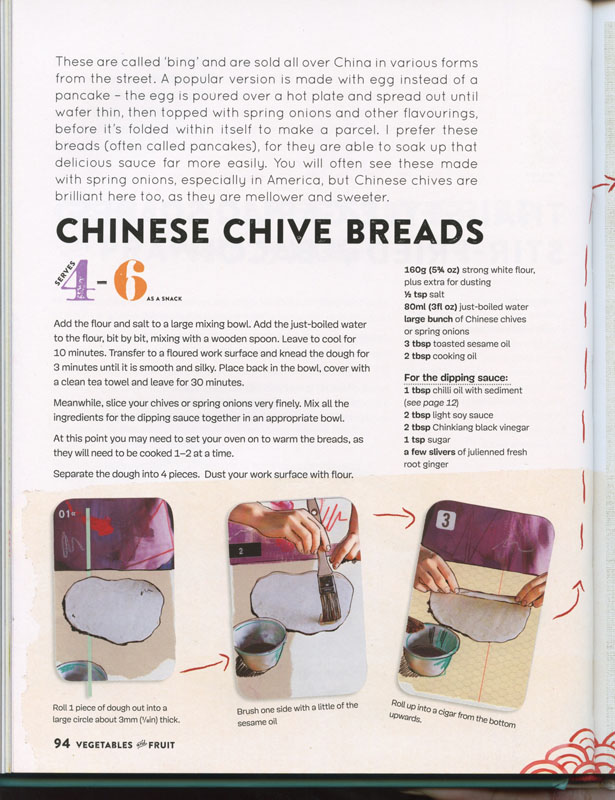

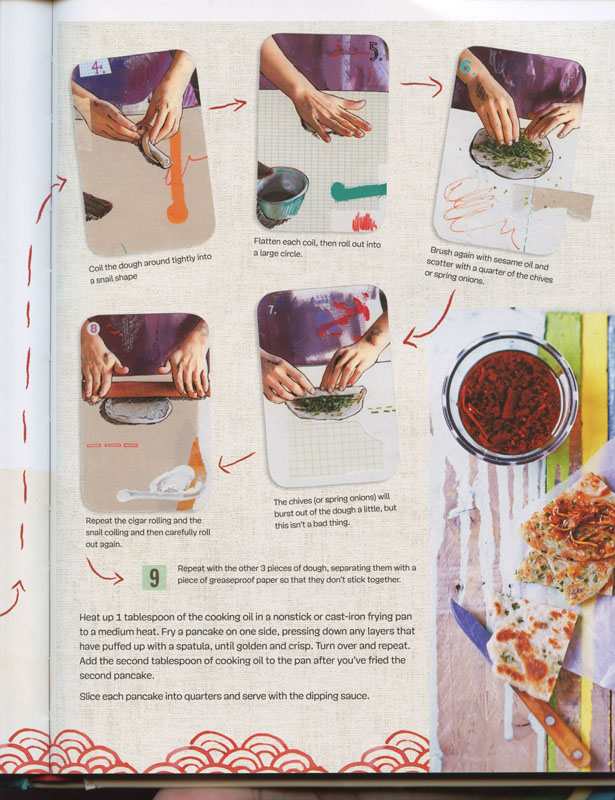

ESEMPIO DI RICETTA