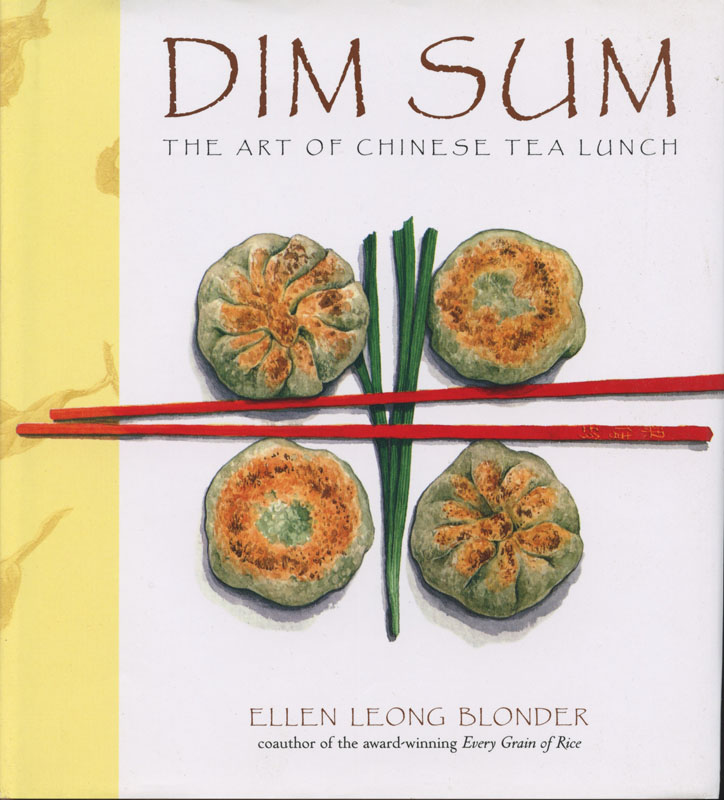

INTRODUZIONE

Dim sum translates loosely as “touch the heart,” which is just what the myriad morsels of a dim sum meal do. While dim sum is usu' ally thought of as a Cantonese specialty, dishes come from many regions: pancakes from the northwest and buns from the north, for example. What began as a mid' to late'afternoon snack has become more often a breakfast or lunch; few restaurants serve dim sum for dinner, although some now offer it well into the wee hours.

At a busy dim sum restaurant, wait' resses jam the aisles with carts bearing small samplings of delicacies, calling out their offerings in operatic singsong. Some carts are piled high with individual steamer baskets; others are fitted with bins to keep stews or rice porridges hot. Still others have griddle tops for pan'frying dishes to order, or glass cases displaying shelves of glistening pastries. On some carts, plastic signs announce the contents, so diners, too eager to wait until a waitress is within earshot, can flag her down.

Yum cha means “drink tea,” or, more

accurately, to have a tea breakfast or lunch with dim sum food. When 1 was very young, 1 used to think having tea and dim sum was the activity of idle, bejeweled ladies pausing in a day of mah'jongg, or of older men sharing a long breakfast over a Chinese newspaper and the latest gossip. After all, the only effort one needed to expend was to beckon a waitress and then nod or wave her away. One could eat for hours from a neverending parade of carts, the waitresses placing dish after dish on the table.

When 1 started searching for a dim sum book that included my favorite dishes, 1 was surprised to find how few existed. Some books contained impossibly elaborate recipes or off-putting ingredients—snow toad fat or plaster of Paris, for instance. Others provided vague or scant English translations. I became intrigued by the idea of writing and illustrating my own. 1 had grown up making a few kinds of dim sum alongside older relatives, but there were many dishes 1 had been eating for years, and 1 wanted to know how they were made.

I grew up within a large constellation of immigrant relatives, and everyone cooked. On a farm far away from Chinatown, we had to make our own dumplings if we wanted dim sum. After helping to make sixty or seventy shrimp dumplings, we chib dren might be rewarded with leftover wheat starch dough to fashion into lumpy swans to float on soy sauce puddles. At that young age, our fingers learned when dough had the right texture, while our palates became familiar with the complex flavors of dim sum. Those early lessons served as the foundation for this book.

1 consulted dozens of cookbooks, recruiting my parents to translate those written in Chinese. Their curiosity was piqued. Cooking test results flew back and forth, and my seventy-nine-year-old father sent me a thirty-page list of food words and cooking terms he wrote on his computer—in English, pinyin Mandarin, Cantonese, and in Chinese characters. My mother queried older relatives and neigh' bors for techniques and advice. I coaxed friends and family into dozens of dim sum restaurants in my local San Francisco area, Los Angeles, Vancouver, and Hong Kong.

One restaurateur proudly told me that on a weekend his restaurant offered more than 100 different dim sum dishes, and that seven men were employed just to make dumplings. Lest this make the prospect of homemade dim sum seem like an over' whelming challenge, bear in mind that no one eats 100 varieties in one sitting.

Most dumpling recipes in this book make about two dozen. If that seems like too many, you may be surprised at how quickly they disappear. Should you have leftovers, keep in mind that many dumplings freeze beautifully. Most need only a final quick cooking, so it is possible to serve a variety of dumplings without working yourself into a frazzle. A few pre- made dumplings also make a delightful treat in the middle of a busy workweek or an easy last-minute appetizer.

COPERTINE

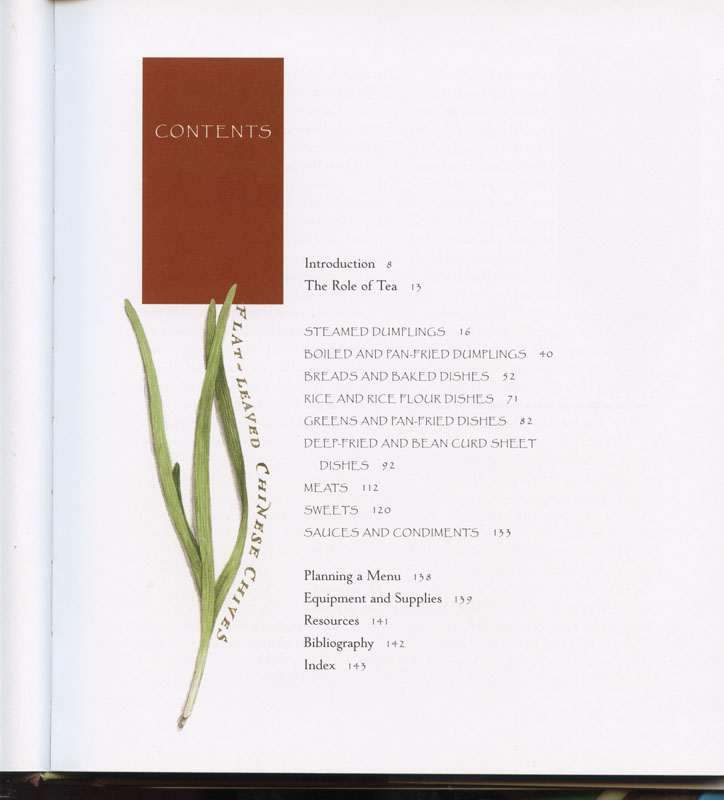

INDICE GENERALE

ESEMPIO DI RICETTA