INTRODUZIONE

Introduction

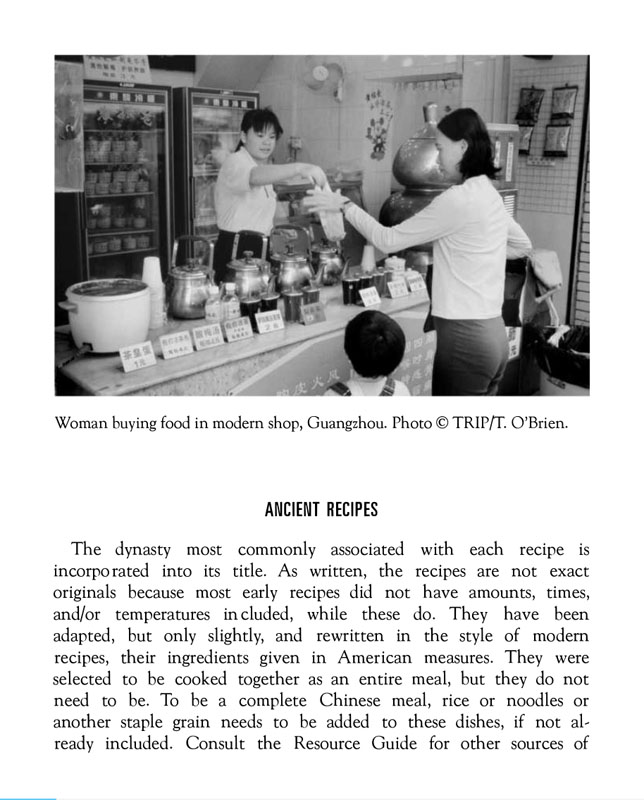

Food Culture in China illuminates the longest continuous food culture in the world, that of the Chinese. It describes foods eaten that have sustained this huge population, foods considered traditional, common, and good. The Chinese believe that eating appropriately is comparable to digging a well before becoming thirsty. Therefore, this book provides background and understanding about a culture that promotes health through eating what the Chinese consider good food and that believes that nothing is more important than eating.

In the 1300s, many Chinese lived to age 70 if they managed to avoid a communicable disease and could afford to acquire their food. What foods and food behaviors contributed to this longevity in an era when most people died near or before the age of 40? Chinese eating habits were considered one and fixed, but clearly the foods of this cuisine have changed and are changing in China and among the Chinese living abroad, so what were and what are their food habits?

With Chinese making up more than one-quarter of the world’s population, each and every day more people are consuming the foods of this cuisine than those of any other cultural group. What food practices did their huge population maintain to survive? This book explores them and the fact that the Chinese gain pleasure from what they eat, speak a lot about their foods, adapt them as needed, and draw strength from them. This volume focuses on the Han, comprising almost 93 percent of the Chinese population.

Readers can gain appreciation of this food culture, one of the two most important cuisines in the world, the other being that of the French. In Chinese food, people have gained cultural health and happiness, and Westerners are now incorporating some of their foods and using some of their culinary techniques, and nutritional know-how. Many and perhaps most of them are variations large and small on what Chinese food really is. With supplies needed to prepare foods of this culture increasing outside of China, there is opportunity to cook what is believed to be real Chinese food and opportunity to understand what it is.

Therefore, this book develops an appreciation of Chinese cuisine. Its chapters discuss the food of China as both cuisine and culture. The historical information increases this knowledge and puts it in perspective. It provides background about the how, where, why, and when of Chinese foods, and details how food-related things came into being.

Ingredients are explored as major food groups, individual foods, and important Chinese food understandings, all major components of Chinese culinary thinking. Cooking in homes and restaurants speaks to what, where, why, and how this culture eats. So does detailing equipment, ordinary and special, needed to prepare their foods. These foundations of Chinese cuisine are the building blocks sitting under regional and provincial food information such as where different cooking styles and different dishes originated and where and how specialty foods play important roles in the food culture, north to south and east to west.

Like its people, Chinese food has roots and wings. The roots of the food culture began before the Xia Dynasty, circa the twenty-first century B.c.E. They have grown many fold. The world recognizes this cuisine as not monolithic; that is, many variations do exist. They are its wings and include but are not limited to the best-known Chinese provincial cuisines of Guangdong, Shandong, Sichuan, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Hunan, and Anhui.

Everywhere in China, people eat individual foods and food mixtures. This book explores Chinese foods and how they are prepared. It looks at particular equipment at home and in restaurants and how the Chinese eat their foods as meals and as snacks. It discusses special foods, including those used at banquets. It details Chinese table manners, current tastes, nationality and family differences, and types of away-from-home eating places; all of these are the food culture of the Chinese.

Eating out is the fastest growing trend in all countries; how the Chinese do this is another facet of their food culture. That is explored with reference to where and when they first ate out and what the forerunners of Chinese restaurants were. Other complexities of eating—such as the cultural protocols for the Chinese and those who join them at their tables, guest responsibilities, how to go and who goes to tea shops, and other food behaviors—are investigated, from those that are static to those that have changed.

Some cultures, the Chinese included, began using the sun and the moon to understand seasons in a given year and throughout many years. This book looks at their solar, lunar, and Georgian calendars and places important Chinese holidays in one or another of them. It delves into festival foods, those used for religious and other rituals, and those that mark family life-cycle celebrations. These parts of the food culture of the Chinese are also detailed, as are Chinese views about nutrition, diet, and health. Illustrating them and some Chinese medicinal and herbal perspectives helps explain some of the ways the Chinese treat their bodies with edible ingredients to keep them healthy and, if need be, to heal them. For centuries, Chinese people have been using specific foods to heal specific conditions.

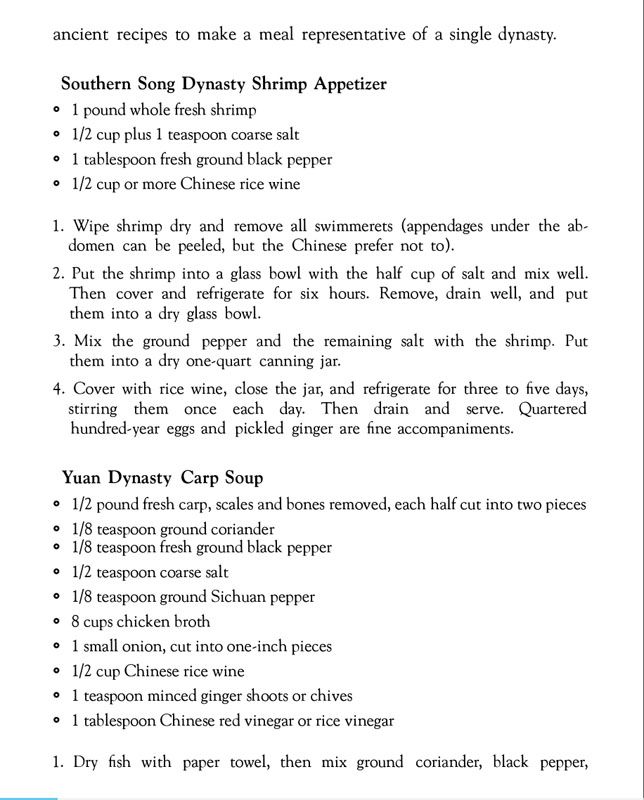

Each chapter in Food Culture in China ends with a handful of recipes selected as illustrative of that chapter’s topics. To make them is to taste content and intent. They are ancient, mid-period, or recent recipes, most made with easily available ingredients. They were chosen so when cooked together they constitute a meal for a family of four to six persons. This assumes the addition of a grain such as steamed rice or boiled noodles, should there be no staple food among the recipes in that chapter. To the Chinese, a meal must have a staple or grain food as its principle component.

Additional parts of Food Culture in China include a timeline of food-related dates, a glossary, and a resource guide and bibliography of mostly English-language references. A selection of English-language Chinese cookbooks is included to provide additional resources for ordinary, banquet, and regional recipes; so are lists of films, videos, CDs, and Web sites.

Savor them all when reading the pages of this book. They explore delicious aspects of Chinese cuisine. Eat Chinese food to gain personal tastes of understanding. Consult individuals and telephone directories for shopping sources that enable seeing Chinese ingredients and cooking them. Visit Chinese restaurants to taste those dishes their owners consider representative of their particular culinary comer of the world. Together, these experiences can expand knowledge of the cultural and culinary contributions that make up the food culture that is Chinese.

Note: Because the Chinese writing system uses characters or ideographs and not an alphabet, this book writes their spoken words in pinyin, the Chinese government’s official spelling system that uses the Roman alphabet. With the exception of some names that still use older transliterations, such as Peking instead of the now accepted Beijing and Mao Tse-tung instead of Mao Zedong, only pinyin transliterations are used in this book.

COPERTINA

INDICE GENERALE

ESEMPIO DI RICETTA