INTRODUZIONE

For most of my life, I bounced back and forth between Singapore and Hong Kong. Whether I was staring across Victoria Harbour on the edge of China, or wandering past street hawkers in Singapore, I was always surrounded by food.

I was thirteen when I took my first restaurant job in Singapore. In the Chinese culture, cooking was not, at that time, something people set out to do so that eventually they could open a three-star Michelin restaurant and conquer the food world. The Chinese kitchen was not a place where people used the words 'genius’, 'creativity' or ‘philosophy’. Cooking was work, like farming or collecting trash. It would not get you an invitation to dinner parties, but it would get you a little money to spend, if you were lucky.

I began working at a restaurant called New Min Ho, but that restaurant soon became more than just a place to work in. I was a kid that needed cash in my pocket and a bed to sleep. Cooking was my way to survive, and the kitchen was my classroom.

I don’t remember learning how to cook; I just started to do it. But I do remember— before my time in the kitchen—cleaning the toilets and washing the dishes. At that time, Singapore was full of hungry young apprentices—youths who would work hard for next to nothing. It was hotter than hell in those tropical kitchens, with open fires, hot stoves and wok smoke, and our shifts were long. The only thing worse than any of that work, was not having any work at all.

Have you éver seen a submarine’s barracks? Our living quarters were like that. We slept in bunk beds stacked together in cramped, poorly lit dark rooms with low ceilings. At that time, all my possessions were stored in a cardboard box. I had come from Hong Kong with next to nothing.

After about a year of washing dishes and scrubbing toilets, I got to gut and fillet fish and chop vegetables—it felt like a breakthrough. At that time, I was not yet passionate about what I was doing—I did not have the ambition of being more than a cook, moving out of the dormitory and eating anything other than the slow-movirig stuff on the menu. It was a simple life, and the restaurant was my safety net.

There was a chef whom I occasionally drank beer with. He took me under his wing and taught me how to make dim sum. This was one of the most valuable lessons I evér learned. His name was Lam, and as long as I bought Lam a drink, he taught me his dim sum-making techniques. He was in his late thirties at that time, and I was fifteen years old.

I worked in the kitchen until I enlisted in the Singapore army, and after two years of - service, I went back to cooking again. The people I served with in the army taught me to think about what I wanted in life. I finally realised that cooking could take me beyond roadside restaurants and seafood shacks. That was my breakthrough. I realised that this life could lead to something better and lead me in new directions, but I had to be the best to go anywhere. I went on to work in three-star hotels, then four, and then five.

I kept moving up, until I became an Executive Chef in 1995.

One rule that I live by now is that I won’t ask anyone to do anything in a kitchen that I haven’t done myself. To understand this business, you need to start at the bottom. From cleaning toilets, to cutting vegetables, roasting ducks and making stock. By the time I was at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Surabaya, Indonesia, I had done it all.

I had cooked in Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand and Brunei. Then my life changed

I became an Executive Chef.

Until then, everything I cooked was based on repetition, on discovering a rhythm and repeating it. Suddenly, for the first time, I found myself with time to think about the food I was cooking; to explore ways of refining it, and to apply the flavours of the places I lived in to my strictly Cantonese regimen. This happened fast, and I finally tasted creativity in the kitchen. It made me who I am now.

I started to tweak the old wrapper recipes for dim sum, adding new ingredients like squid ink, after I saw the Italians do that with pasta. I thought about-cold desserts and how they could be altered. Once, I fried guiling gao, a traditional herbal jelly and served it hot and crisp, with honey drizzled on top. I wasn’t reinventing, but innovating. All I do is take a dish and think, can this be different? Can it be more delicious? Can it be more stimulating when eaten, but retain its character? I appreciate all kinds of food, but I am a Chinese cook, and so I keep my dishes Chinese. I learnt a lot in those years when I travelled and did demonstrations in Europe, the US, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore.

I started to think about people’s palates, how they changed from place to place, and how to plate food in a pleasing way.

In a world full of Chinese chefs, it's hard to stand out. I discovered how to do that, and everything changed from that point. In a cuisine that is defined by tradition, I made a name for myself through small innovations. That was it. I started to win awards and people began to talk about, my food. It was flattering, but there was something missing—that gaping hole in my resumé. I had never cooked in China, my ancestral home and the place where all my cooking originated from.

Instead, China came to me. I was running the Cantonese restaurant at the Four Seasons Hotel in Singapore, when three guests asked to see me. They offered me a job at Three on the Bund in Shanghai. It was touted to be a groundbreaking, new project.

It took a tot of convincing for me to leave the Four Seasons for the Bund, as the project was still in its infancy. But with the lure of Shanghai, I decided to go—and the Whampoa Club was bom. The first time I saw the Bund, I felt like I'd been transportecf back a hundred years, and it really looked like the Paris of the Orient, as it was once called. I guess I'm not the only one who feels that way when they see it.

The food in Shanghai was another story. For the first three months, everything was good—it was my Chinese honeymoon. But after a while, I realised that the food had its own character, but it wasn’t something I enjoyed. So I set myself to work—studying old recipes and tweaking them into a more refined style of Shanghainese cooking.

I never imagined that news of this restaurant would travel as far as it did, or as fast.

Soon, I was featured in newspapers such as the International Herald Tribune. People

were talking about Whampoa Club as Shanghai was in the limelight all over the world.

We were in the right place at the right time, we were working as hard as we could, and we did it. Suddenly, we were the most talked-about Chinese restaurant in China. And it only took two years for that to happen.

After operating Whampoa Club for three years, it was recognised as one of China’s top restaurants. From Shanghai, we went on to open branches in Surabaya, Indonesia, then Jakarta, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, and Singapore. In 1995, we were the top Chinese restaurant in Surabaya. I had success. I knew I was doing something right, and I knew how much research I had to put into cooking this food.

In China, Beijing was a natural progression after Shanghai. The Olympics were coming, the government was there, the money was there—China was there. We went back to the drawing board, and we made battle plans. I bought an apartment in Beijing. I started to eat like crazy to research recipes, take photos and make notes, and take in all that was related to Beijing cuisine.

I realised that Sichuan food was everywhere! So was Dongbei food, and likewise the Inner Mongolian hotpot, Yunnan, Hunan and Xinjiang cuisine. The diners cared less about style and more about tradition. There was a great quality and heartiness, an honesty about this cooking one might not find in Shanghai. For Beijing cuisine, the climate and ‘comfort’ quality shaped it. It was food for hot summer days and frigid winter nights. Hot and cold, sweet and sour, light or very heavy.

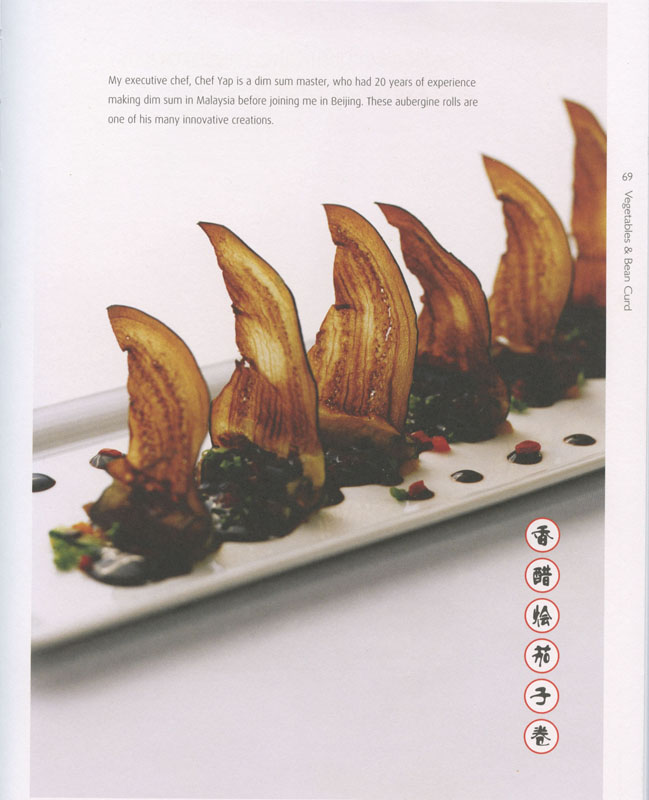

In the following pages, you’ll see the results of my Research in Beijing, and recipes from my restaurant there. Together with my Executive Chef, Chef Yap, I've tried to capture the essence of Beijing cuisine—recreating many of its renowned dishes, with a>nod to tradition and subtle updates in style. Butto cook these dishes, you must first understand their background, to appreciate why we interpreted them as such. Jarrett and I have explained this in the recipe headnotes.

In some ways, my Beijing story is not unlike the story of modern Chihese food in Mainland China. For many years, it was a utilitarian thing. People cooked and ate, and nothing more was expected than that. But times have changed, China has changed, and its food is evolving too. I am proud to be a part of this change.

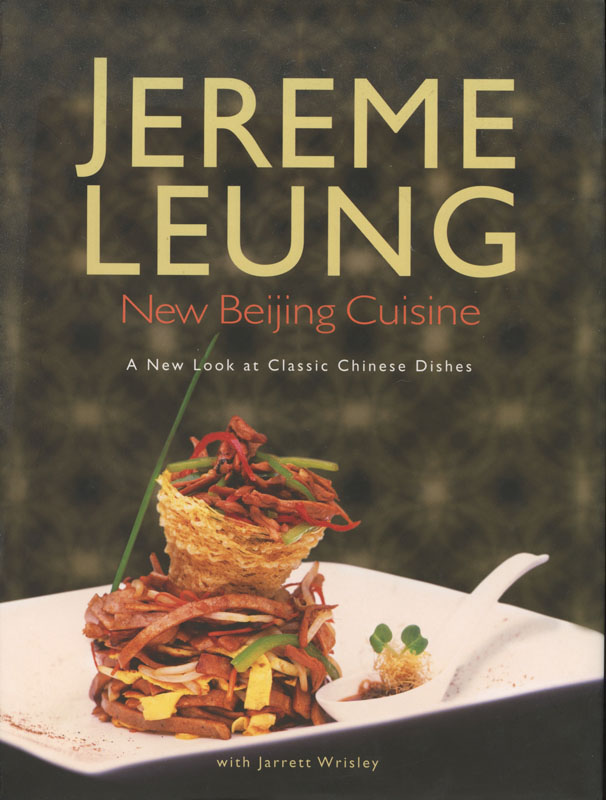

COPERTINA

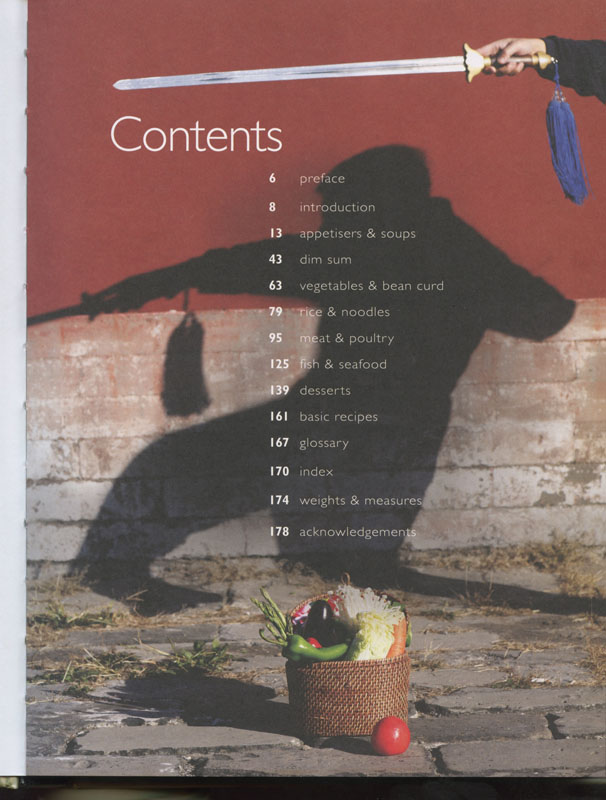

INDICE GENERALE

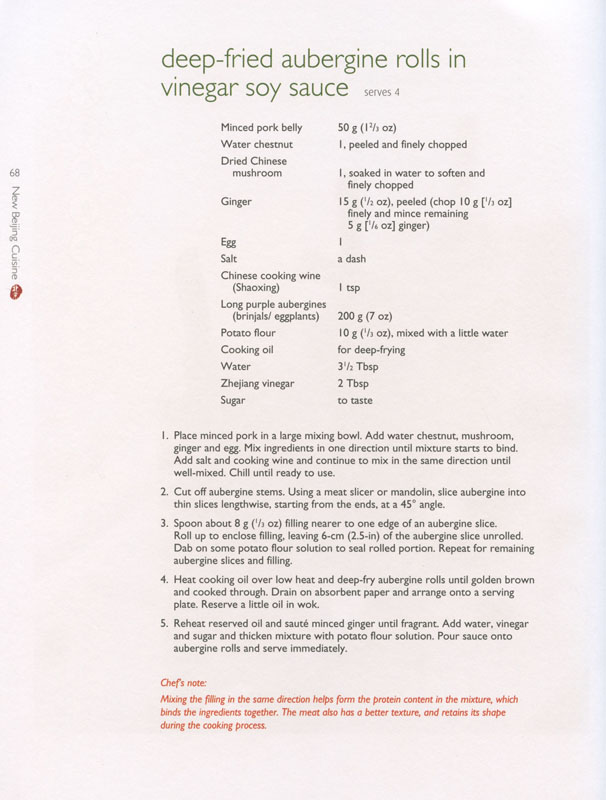

ESEMPIO DI RICETTA