di Terry Tan

LA CUCINA

Chinese regional cooking can be said to fall into four categories that roughly correspond to the four points of the compass: north, south, east and west. However, since it is in the nature of cooks to enjoy sharing ideas and recipes, these distinctions are not clear-cut. The northern school of Chinese cuisine is often termed Mandarin cuisine or Beijing-style cooking. Each individual province has its own food history and collection of recipes, but they have influenced each other for many centuries, with similar ingredients dotting the menus.

A Tang Dynasty official once said, "There is nothing that cannot be eaten. Making things edible is only a question of skilfully blending sweet, sour, bitter, salty and peppery flavours while cooking." He was said to have stewed an old saddle and declared it very tasty. Apocryphal perhaps, but the story certainly sums up Chinese attitudes to food.

Beijing cuisine

The focus of northern Chinese cuisine is, of course, the Beijing school. Due to its imperial heritage of excess and affluence, Beijing cuisine came to be regarded as the most sophisticated yet robust style, using simple ingredients in an elaborate way. The elegance of Beijing cooking may

not be apparent to the uninitiated; its simplicity masks clever techniques and a close understanding of the best produce of the region. Beijing cuisine is more influenced by the vast hinterland of Mongolia and beyond than it is by the sea on its eastern shores. Menus are thus rich in lamb, game and poultry, roasted or barbecued to tender perfection, as well as some fresh fish and shellfish from the ocean and rivers.

During the Manchu Dynasty, some 2,000 chefs were employed in the palace kitchens of the Forbidden City.

The kitchens were divided into separate departments to make special food for picnics and travelling (emperors journeyed far and wide surveying their

kingdom), and dawn and dusk sacrifices (Taoism and ancestor worship ruled the Chinese household), as well as having divisions just for rice and noodles, pickles and so on. Modern Beijing chefs are proud of their traditional hand-tossed noodles, and in the streets of Beijing you can still see noodle sellers dexterously balancing lumps of dough in their hands, kneading and transforming them into noodles before your eyes.

Below left Cattle and sheep graze on the verdant plains of Hebei province, just outside the municipality of Beijing.

Below Farmers harvest a successful crop of wheat In the fertile countryside of Shandong province.

Above A fisherman uses traditional methods to break the ice on a frozen lake in Heilongjiang province, ready to fish during the long, harsh winter.

Further afield in northern China

The culinary traditions of this region include recipes from as far north as historical Manchuria, all the way down to Henan and Shandong.

The chief characteristic of northern cooking is the frequent and lavish use of soy bean paste. This is the basis of many other pastes, such as hoisin and yellow bean, which are used to enrich sauces. Chefs in the northern regions attach great importance to the use of fresh meat and young vegetables because in the harsh terrain, with difficult transportation and no refrigeration, each region was forced to maximize the use of local products. Historically, rice was not used in northern China, but in more recent decades, due to modern transportation, northerners have discovered the versatility of this grain and adapted some of their traditional dishes to include rice.

Shandong cuisine is one of the most influential in China. The Beijing school, as well as other northern provincial

styles, is thought to be a branch of Shandong style. Seafood is common, as well as wheat, millet, and other grains Steamed breads are the choice staple.

Tianjin shares a similar cuisine with Beijing, though it uses more fish due to its coastal location. The flavours here are less heavy and rich than in Beijing.

Heilongjiang is a province criss-crossed by rivers, and its cuisine is famed for its fish dishes. Liaoning cuisine is derived from traditional native cooking styles,

but it is also heavily influenced by Beijing and features strong tastes with much interplay of sweet and sour flavours, winters here can be severe, resulting in a short growing season, and the relatively difficult climate has helped to shape the cuisine. Most dishes are rich and hearty, with wine sauces and bean pastes. The cooks here coax much from wheat, millet and soybeans, transforming them into a wide range of breads, noodles and other starchy fillers that insulate the body against the cold winter weather.

Preserving food

Jilin cuisine relies heavily on preserved foods and hearty fare owing to the harsh winters and relatively short growing seasons. Pickling is a common method of food preservation, and many households have large urns of pickled cabbage or mustard greens steeping away in their kitchens, as they do in Korea just across the border. Noodles tend to be the most common staple in Jilin cuisine.

COPERTINE

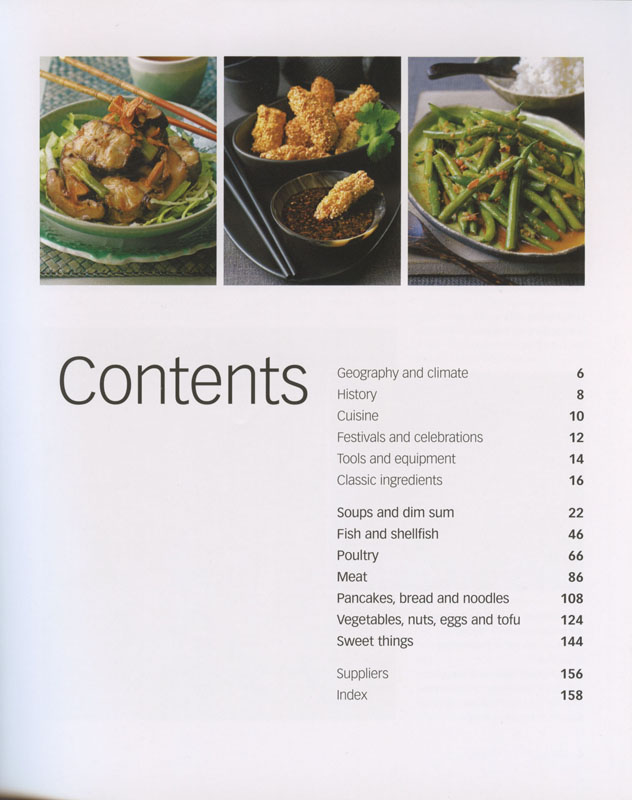

INDICE GENERALE

ESEMPIO DI RICETTA