INTRODUZIONE

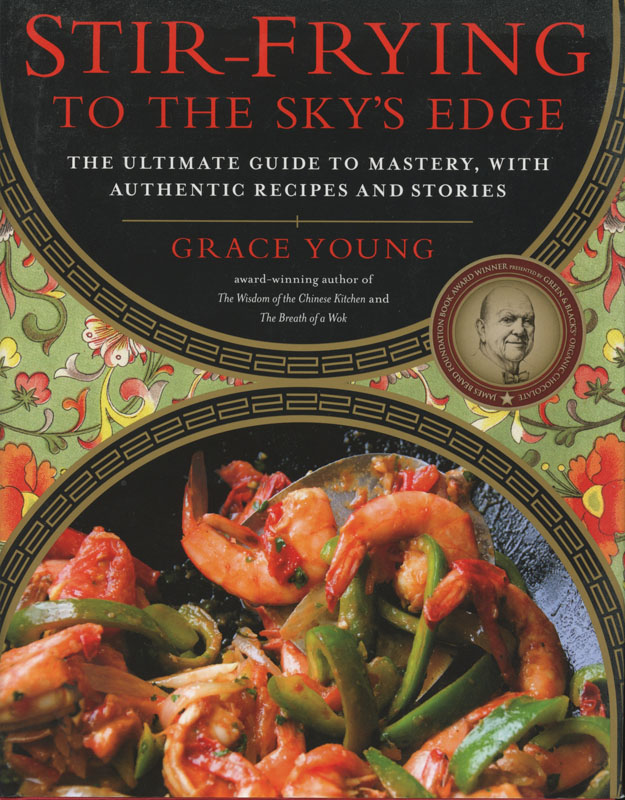

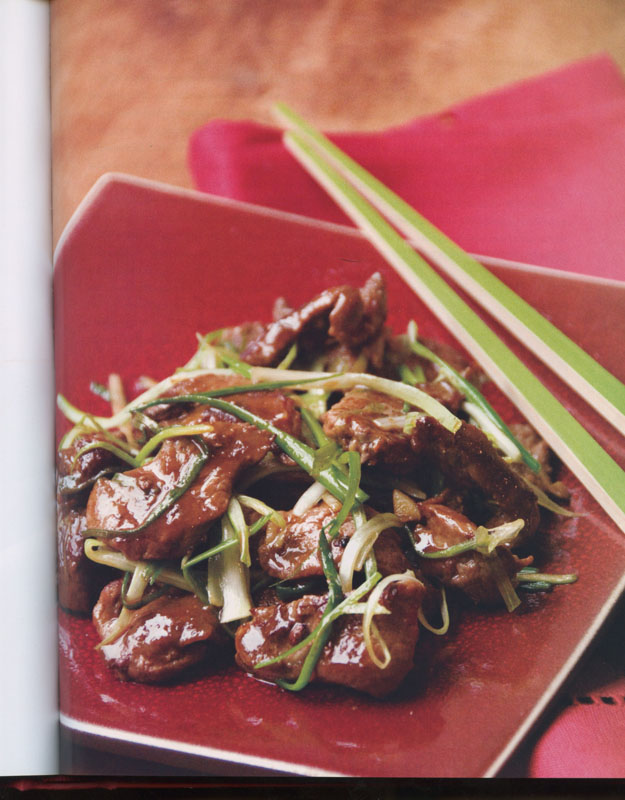

I consider stir-frying a form of culinary magic in which ingredients are transformed. Their textures are enhanced, their flavors intensified and caramelized. The alchemy of stir-frying brings a blush of color to raw shrimp and a radiance to vegetables. Meats grow plump and fragrant from browning. The stir-fry dish brings food to life.

I grew up observing my father’s passion for stir- fries, developed from years of frequenting the best restaurants and knowing many of the great chefs in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Later, I developed my own more consuming infatuation, because it wasn’t enough for me to appreciate the pleasures of a delicious stir-fry: I needed to know how it was made.

Over time my esteem for stir-frying has only grown. I see it as a way of life, both timeless and timely. As I’ve observed rising food and fuel prices, I cannot think of another cooking technique that makes less seem like more, and by which small amounts of food feed many. And what could be healthier than cooking with a minimum of meat and fat and emphasizing vegetables of every kind?

This book is about a “universal longing for home” and a cooking technique that traveled the globe satisfying that desire. The story of stir-frying is one of cultural perseverance and healthy, flavorful cooking, of universality and subtle distinction, of the Chinese diaspora and local character. Each of the many cooks I interviewed lends a human face and personal technique to the vast stir-fry tradition. In the hot, tropical Malaysian village of Dungun, stir-frying enabled

Mei Chau, a young girl entrusted with feeding her family, to produce flavorful dishes while being mercifully delivered quickly from the intense heat of the kitchen. In the Caribbean, Winnie Lee Lum continues the culinary traditions her parents brought with them in the 1930s when they emigrated from China to Jamaica, as well as integrating the local ingredients and techniques she has learned from living in Trinidad for over forty years. In Redwood City, California, Fah Liong stir-fries the same simple Hakka dishes her mother taught her in Indonesia, substituting American vegetables for the Asian produce she once used. The common theme of all the stories and recipes in this book is the transformation of humble ingredients into rich, delectable, healthful meals using precious little food and cooking fuel. Regardless of whether it is a ten-year-old child who learns to stir-fry when her mother falls ill, or a ninety- year-old woman who partners with her son-in-law to stir-fry, each cook demonstrates how, if you have only tasted a stir-fry in a restaurant or cooked from a recipe taken off the Internet, you have missed the humanity of stir-frying.

I grew up in a very traditional Chinese home in San Francisco where my parents cooked the same Cantonese dishes they had eaten in their youth in China. My ideas of Chinese food were based on a strict adherence to classic food combinations that left no possibility of improvisation. For example, my mother would always stir-fry ginger with Chinese broccoli (page 190), never garlic. One of my favorite dishes she stir-fried was ginger tomato beef (page 80), a recipe she never considered making with chicken or pork. In our household, Chinese recipes were carved in stone.

Imagine my revelation at Flenrica’s, a Chinese Jamaican restaurant in Rosedale, Queens, which is part of New York City. When perusing the menu of unremarkable Chinese American dishes, my eyes fell upon a listing for Jamaican jerk chicken fried rice (page 262) and then one for jerk pork fried rice and for jerk chicken chow mein. Jerk chicken in a Chinese stir-fry? To my great surprise, the dish was wonderful—the spicy, robust jerk chicken was beautifully suited to the rice flavored with soy sauce and speckled with chopped onions, scallions, and finely diced carrots. I asked to meet the chef and was led into the kitchen where, side by side, a Chinese and a Jamaican chef worked at the stove. When I asked the Cantonese chef how he made the jerk chicken, he shrugged his shoulders and nodded to the Jamaican chef who, it turned out, cooked the chicken that he then turned over to the Chinese chef to stir-fry with the rice.

Not long after my visit to Henrica’s, I was introduced to a Chinese Guyanese restaurant called Happy Garden in Jamaica, New York, where jerk chicken fried rice appeared alongside Guyanese dishes and typical Chinese American ones. Then I heard about a Chinese Indian restaurant in New York City called Chinese Mirch. There I sampled wildly spicy Sichuan vegetarian fried rice (page 265), made with basmati rice, and Chicken Manchurian (page 142), a scrumptious stir-fry generously spiced with fresh chilies. The Indian American owner brought me into the kitchen to meet his Cantonese chefs. He explained to me his cooks were trained to use the Chinese stir-fry technique, but with ingredients suited to the Indian palate and without the pork, beef, rice wine, or alcohol that are prohibited, in accordance with Muslim and Hindu dietary laws.

When I came across Chinese Restaurants, a fifteen- part documentary series produced by Cheuk Kwan, a Chinese Canadian documentary filmmaker, I was fascinated to follow Kwan’s exploration of Chinese restaurants in such unlikely places as Mauritius, Turkey, Argentina, Trinidad, and Israel. In my naiveté it had never occurred to me that the Chinese had immigrated to such disparate countries. In fact, seven and a half million Chinese left southern China at the beginning of the nineteenth century because of economic poverty, with the vast majority remaining in Southeast Asia. Chinese migration continues to this day to the far corners of the globe. I began to ponder whether Chinese immigrants living abroad learned to adapt their cooking to local tastes and if they always continued the traditions of stir-frying. Were there other stir-fries like jerk chicken fried rice, invented when the tastes of two cultures merged?

My search for stir-fry recipes ultimately evolved into an almost anthropological examination of the Chinese immigrant experience worldwide as expressed through the stir-fry. I visited restaurants that served Chinese Peruvian, Chinese Mexican, Chinese Dutch, Chinese Guyanese, Chinese Indian, Chinese German, Chinese Vietnamese, Chinese Jamaican, Chinese Cuban, and, of course, Chinese American food, observing that these unique Chinese restaurants had learned to adjust their cooking to cater to the mainstream tastes of their clientele. I located Chinese whose families had immigrated to Peru, Trinidad, New Zealand, Fiji, Indonesia, Jamaica, Libya, Holland, India, South Africa, Burma, and Germany. I conducted cooking interviews and tasted stir-fries that fused various culinary traditions. These interviews often revealed the unimaginable hardships experienced by Chinese immigrants living without Chinese communities. Many of the people I met recounted how a stir-fry’s aromas and tastes eased their sense of displacement, providing comfort as they adapted to foreign customs, language, and climate. Often cooks had to simplify classic dishes; at other times they substituted, embellished, or combined local ingredients and the popular tastes of their new culture with intriguing and mixed results. Some families even learned to grow Chinese vegetables and make their own tofu.

I even became fascinated by the language of stir- frying. The distinct tossing and turning action of stir-frying captures the notion of quick change and is used in several Cantonese terms for speculation, as in “stir-frying stocks” and “stir-frying real estate,” the buying and selling of stocks and real estate for quick financial gain. Surprisingly, “stir-fry” even appears in a number of colloquial expressions that have nothing to do with change or quick movement—such as “to stir-fry a person,” a slang term for firing an employee. The Cantonese obsession with stir-frying inevitably leads to a discourse on wok hay, the Cantonese term that refers to the distinct vitality exuded when super-fresh ingredients are stir-fried so perfectly they possess wok fragrance.

I interviewed Chinese whose families were among the first to settle in towns in Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arkansas, and Tennessee. For many, their only means of earning a living was to open a restaurant serving Chinese American fare that included chop suey, the crude “non-Chinese” stir- fry improvisation that became a staple for Americans and provided for Chinese economic survival. Eventually I interviewed Chinese who had beeln raised in the Mississippi Delta in the 1930s and ’40s. The story of the Chinese of the Mississippi Delta is one of the most remarkable testaments to the tenacity of Chinese immigrants anywhere. Brought to the South as laborers in the 1870s, and often living in towns in which they were the only Chinese residents, these immigrants gradually began running grocery stores throughout Mississippi that serviced impoverished sharecroppers. Without a wok and with limited Chinese ingredients, these Chinese used local produce, such as rutabagas or turnip greens, plus a little salted pork and a frying pan to re-create their longed-for stir-fries.

Stir-frying has been a continuous comfort to the Chinese diaspora. Even when deprived of Chinese produce, condiments, and the wok, the Chinese have always managed to find a way to stir-fry.

I have tasted my share of mediocre stir-fries. It is easy to produce uninspired dishes when stir-frying is approached with the attitude that it is merely the quick cooking of bite-sized pieces of meat and vegetables in oil with no sense of its refined artistry. In this cookbook I share with you all the stir-fry principles and knowledge I have learned from home cooks, master chefs, and cooking teachers from around the world. I offer detailed recommendations on all aspects of stir-frying at home, focusing on the challenge facing most cooks: working with stoves that do not produce the ideal amount of heat for stir-frying.

In truth, stir-frying is a cooking method of great subtlety and sophistication. In Chinese cuisine a system of classifications exists to distinguish “dry” from “moist” stir-fries (depending on whether broths, sauces, or liquids of any kind are added). The term “clear stir-fries” is reserved for ingredients that have been stir-fried in a little oil and deftly seasoned, thus enhancing the pure essence and character of the main ingredient. “Velvet stir-fries” involve the coating of an ingredient, such as chicken breast, in an egg white and cornstarch mixture, which is then blanched in hot oil or water and stir-fried until the texture becomes silky and succulent.

Stir-frying is a technique of tradition and innovation. This cookbook mainly comprises classic stir-fry dishes from the traditions of Guangzhou (Canton), Hong Kong, Shanghai, Fujian, Sichuan, Hunan, and Beijing. These recipes are the essentials for any stir- fry repertoire. In addition, there is a small selection of recipes from the Chinese diaspora in India, Trinidad, Jamaica, Cuba, Singapore, Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, Burma, Vietnam, Macau, Peru, France, and America, reflecting the borrowings of another cuisine. The subject of the diaspora and their experiences with stir-frying is vast and cieServes its own study. These singular recipes give you a sense of how the stir-fry, the supreme culinary chameleon, can bring together the tastes of one culture through the ingredients of another. For cooks who feel they cannot stir-fry because they lack Asian ingredients, these resourceful, clever combinations are living proof that with ingenuity the improvisational possibilities are infinite.

Stir-frying can be enjoyed both for its time- honored recipes and its innovative modern ones, and for the promise it offers to create new classics. The Chinese stir-fry is all things: refined, improvisational, adaptable, and inventive. There is an old Cantonese expression, “Yad wok jao tin ngaai, ” or “one wok runs to the sky’s edge,” meaning “one who uses the wok becomes master of the cooking world.” For centuries the Chinese have carried their woks to all corners of the earth, continuously re-creating stir- fry traditions. Today, the sky’s edge extends beyond geographic borders into cultures newly integrated with all manner of popular and ancient ways. Stir- frying’s innumerable possibilities for creating simple, nourishing, and wholly satisfying meals that feed the body and nourish the soul await.

COPERTINE

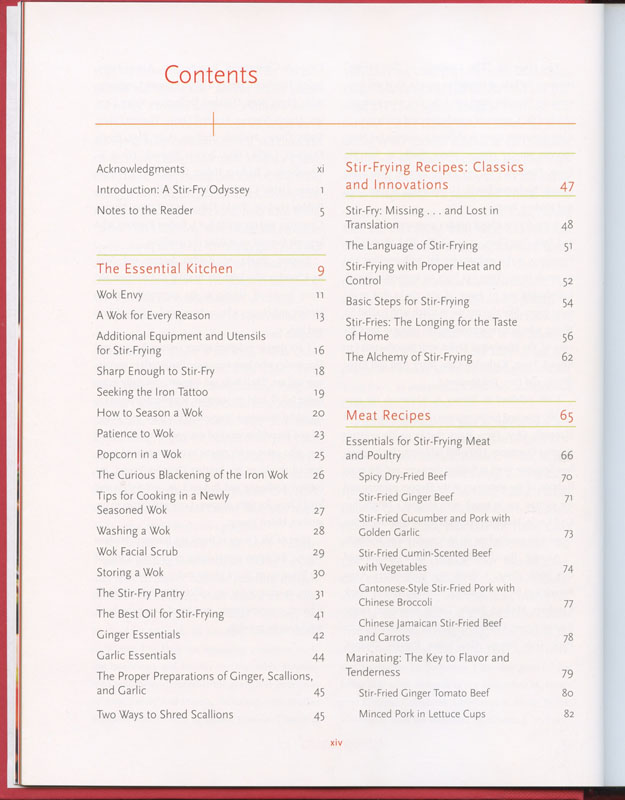

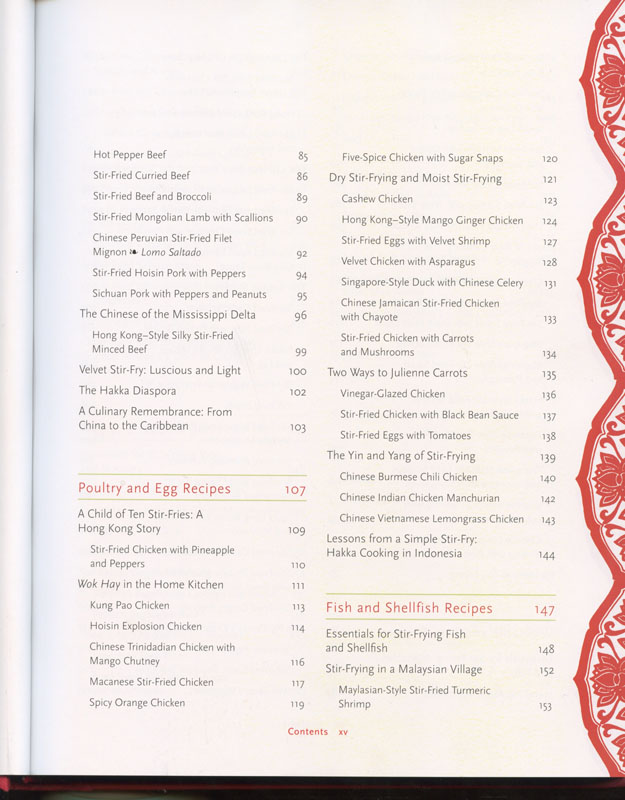

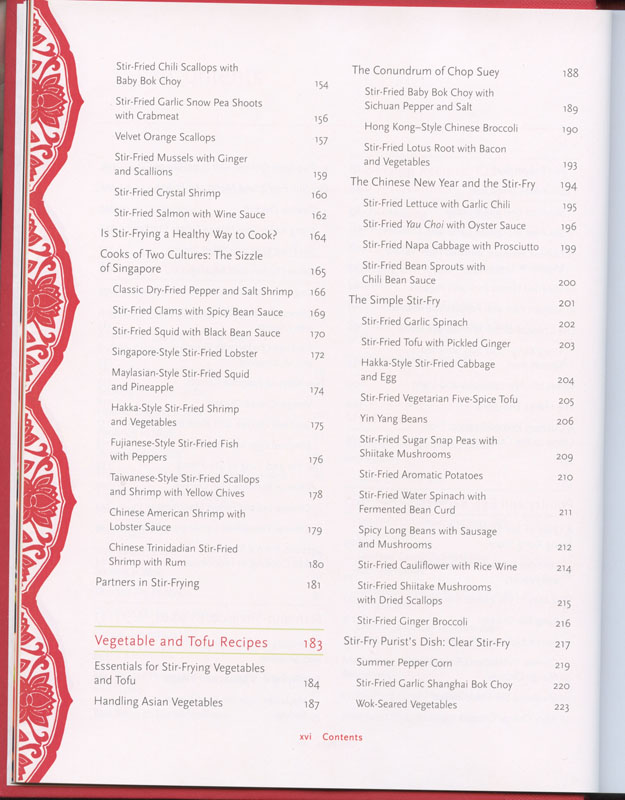

INDICE GENERALE

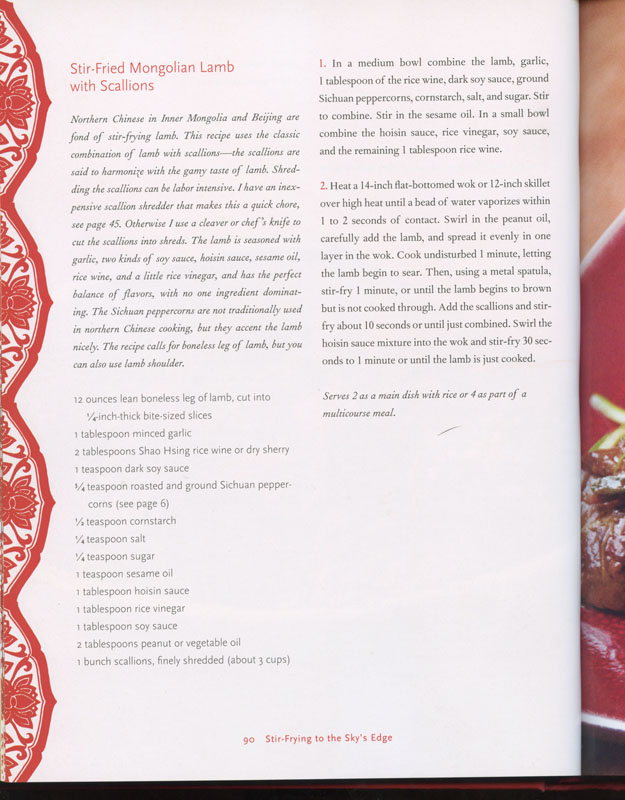

ESEMPIO DI RICETTA